Human taste preferences and adaptations

Author:

Hellen Dea Barros Maluly (MALULY, H.D.B.)

Pharmacist and PhD in Food Science. Access this CV at: http://lattes.cnpq.br/2754275781355863

Published on: 2 de July de 2021

Abstract

There is a lot of science involved in the process of sensitivity to basic tastes. The gustatory system works in synchrony with the other senses, which respond to various stimuli from the environment. The combination of these factors can determine whether or not food is accepted.

Palavras-chaves: taste, flavor, taste buds, receptors, umami, food acceptance

Perceiving basic tastes, such as sweet, salty, sour, and bitter, is already an automatic and quite common act. The fifth taste, umami, is still not recognized by many, but this may be due to its Eastern identity. All of these tastes are present in various meals in our daily lives, and the scientific community has shown interest in the topic for some years and has already been able to reveal the mechanisms of action involved when a substance comes into contact with taste cells (Beauchamp & Jiang, 2015).

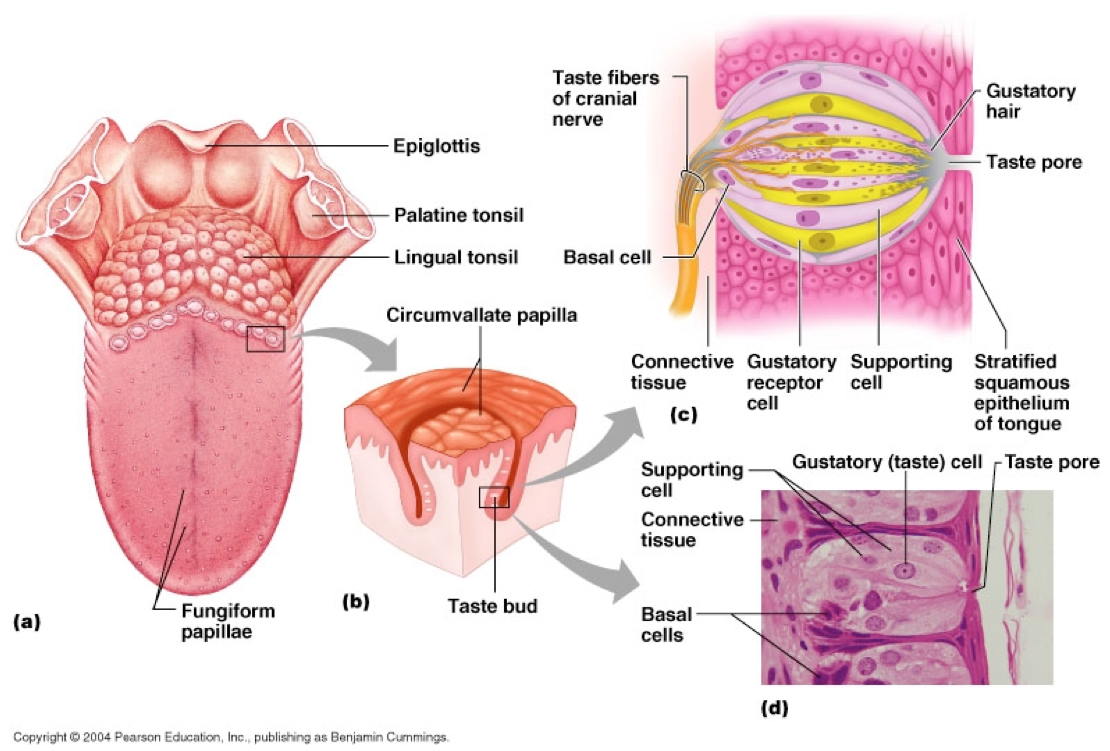

Taste cells are located in specialized structures known as taste buds. These cells are located in taste buds, which form projections of cells similar to small fingers that project out of the taste bud through an opening called a taste pore (Chaudhari & Roper, 2010).

For a long time, scientists believed that the taste buds for each basic taste were concentrated in different regions of the tongue, each specific to a different taste category. However, more recent studies show that these buds are distributed randomly throughout the dorsal area of the tongue, without boundaries, and in smaller numbers throughout the soft palate and epiglottis (Feher, 2017).

Other information currently considered by scientists relates to human behavior regarding basic tastes. It was long reported that bitter taste was linked to the recognition of substances that are harmful to humans, and to some extent it still is. However, we have had incredible discoveries that have shown that many bitter substances do not cause harm in certain concentrations and can even provide pleasure, such as those present in beverages like hoppy beers and the “Negrone” drink, made with gin, vermouth, and Campari. It was also believed that sweet taste was stimulated only by carbohydrates, but now other molecules are recognized that can confer this pleasant sensation without introducing calories into meals. Salty taste is provided by sodium, potassium, and other ions, and most interestingly, scientists have identified a specific ion channel exclusively for sodium. Both sweet and salty tastes have also greatly influenced human taste, leading government agencies to institute measures to reduce these ingredients in foods. Sour taste, stimulated by acids present in food, was also recognized as something bad, as in the early days, humans associated this taste with spoiled food. But, like bitter taste, important acidic substances are considered palatable, tasty, and nutritious. Umami taste, on the other hand, is perceived when amino acids and nucleotides in food interact with specific taste receptors and may symbolize the taste of proteins, but this fact was only truly confirmed in the mid-2000s (Beauchamp & Jiang, 2015; Niki et al., 2010).

Unlike sour and salty tastes, which interact with their respective ion channels, sweet, bitter, and umami tastes interact with taste receptors coupled to G-proteins**, and several reactions occur to trigger membrane depolarization—a slight electrical discharge that activates taste innervations (Chaudhari & Roper, 2010).

In the case of umami taste, the presence of receptors on the tongue that respond to the presence of glutamate, specifically through mGLUR4, has been observed (Chaudhari et al., 1996).

Other molecular studies have already shown the presence of other types of receptors involved in the detection of Umami. These are the T1R receptors. These respond to most of the 20 basic amino acids and are therefore fundamental in functions such as protein building and metabolic fuel. Furthermore, the T1R1 and T1R3 subunits, when joined (also called T1R1+3), constitute the Umami taste receptors and are selectively activated by glutamate and nucleotides (Feher, 2017).

Within this entire sensory science, it has been observed that these factors can help in studies of consumer preferences or specific populations and also offer food alternatives that concentrate a diversity of basic tastes so that the population’s palate does not become monotonous and diets become healthier and more enjoyable.

* Receptors are protein structures located in the cell membrane or cytosol that allow the interaction of certain substances called signaling molecules, which will trigger specific metabolic reactions. These molecules promote an anatomical change in the receptor, triggering the transformation of the signal by the cell’s cytoplasm. In this system, receptor activation leads to the release of calcium ions from internal cell reservoirs, and these signal gustatory perception to nerve endings, with the message being interpreted as a taste.

**G Protein: G proteins are so called because the genes that encode them are members of a superfamily of genes that encode proteins that bind to guanine nucleotides with high affinity and specificity.**

References

- Beauchamp, G.K.; Jiang, P. Comparative biology of taste: Insights into mechanism and function. Flavor 2015, 4 (9).

- Chaudhari, N; Yang, H; Lamp, C; Delay, E; CartFord, C; Than, T; Roper, S. The Taste of Monosodium Glutamate: Membrane Receptors in Taste Buds. The Journal of Neuroscience, June 15, 1996, 76(12):3817-3826.

- Chaudhari, N; Roper, S.D.The cell biology of taste Vol. 190 No. 3, August 9, 2010. Pages 285–296.

- Feher, J. The chemical senses. In: Feher, J. Quantitative Human Physiology: An Introduction. 2 ed. London: Elsevier, 2017.

- Niki, M; Yoshida, R; Takai, S; Ninomiya, Y. Taste and Health: Nutritional and Physiological Significance of Taste Substances in Daily Foods. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 33(11) 1772—1777 (2010)